There are a few things that make up the soul of a city: its people, its cuisine, and its architecture. Recently, a 1920s house in Terrell Hills designed by architect Atlee Ayres hit the market. In the listing, it was noted that Ayres had designed hundreds of home across San Antonio in the early 20th century, including the Atkinson-McNay House, along with famous commercial buildings such as the Freeman Coliseum and the Smith-Young Tower, once the city’s tallest skyscraper. If architecture defines a place, then Ayres was key in creating the San Antonio we know today.

But despite his reputation as “San Antonio’s most famous architect,” there isn’t much written about Ayres (in fact, there’s only one book — The Eclectic Odyssey of Atlee B. Ayres, Architect — dedicated entirely to his legacy). Adding to the confusion is that often what is written is incorrect, due largely to his longtime partnership with his son, Robert M. Ayres, leading to confusion about exactly which Ayres is responsible for which project.

“He hasn’t been discovered by the right people,” explains University of Texas at San Antonio professor emeritus Maggie Valentine. “And people confuse his work with his son.”

Ayres’ approach, one that was heavily influenced by the Spanish Colonial buildings found in Mexico, California, and Florida, makes him what Valentine calls one of the “truest examples” of Southwestern Neoclassical architects. And because his 71-year career was as long as it was prolific, there are hundreds of examples to be found around the Alamo City, from Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph’s iconic “Taj Mahal” building to a charming 1950s pool cabana featured in Architectural Digest.

In total, Ayres designed 500 buildings, and many of the characteristics of those projects — tile work, stucco, columns, raised houses to increase circulation, two big rooms on either side of a home with a hallway down the middle — have become synonymous with San Antonio’s “look.”

“[Ayres’ work] is extremely good quality. He follows the rules, he knew what he was doing. He borrowed from classical and he did it very well,” says Valentine.

Looking southwest from Medical Arts Building toward steel framework of Smith-Young Tower in 1928. Published Oct. 9, 1928, in the San Antonio Light: “Skyline view from Medical Arts building showing how Smith-Young Tower on Bowen’s Island, 35-story skyscraper, looms up above the business district skyline.”

UTSA Special CollectionsEnchanted by San Antonio

The Smith-Young Tower as shown in 1929, the year it opened. Now known as the Tower Life Building, it remains an iconic piece of the San Antonio skyline.

UTSA Libraries Special CollectionsAtlee B. Ayres was born in Ohio in 1873 and moved with his family to Houston in 1880 before settling in San Antonio in 1888. The Ayres family lived “directly across the dusty plaza from the fabled Alamo in a three-story limestone building,” writes Robert James Coote in The Eclectic Odyssey.

Coote writes that Ayres was enchanted with his new home, inspired by the “winding streets, old structures of Spanish origin, and chili stands on the various Plazas which were illuminated at night with varied colored lanterns, and the large wood fires heating the food and the chili queens in costume.”

As a young man, he left San Antonio to study at the Metropolitan School, then part of Columbia University. While studying in New York, Ayres learned the “classical, disciplined design foundation” that would come to influence so much of his work, and in turn, the city’s aesthetic.

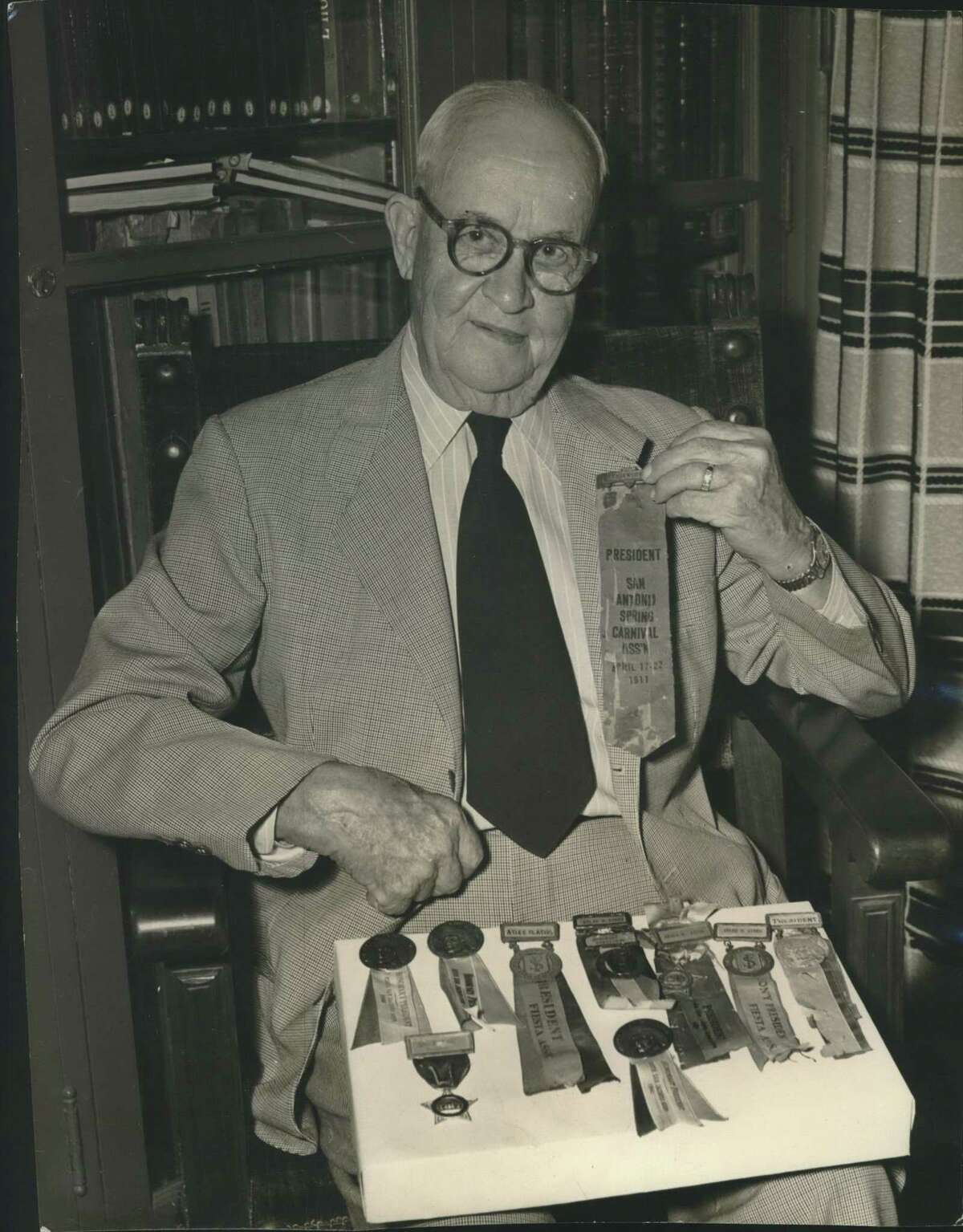

Atlee B. Ayres, president of the Fiesta Association 1911-1918, directed a “womanless wedding,” a burlesque of pageantry staged April 18, 1918, during Fiesta. Ayres cast himself as the bride. The formal Order of the Alamo Queen Coronation had been cancelled because of World War I; the all-male revue was about the only note of frivolity for Fiesta that year.

/Elicson PhotographyAfter he graduated from the Metropolitan School, Ayres moved to Mexico City in 1894 for 18 months before returning to San Antonio and opening his architecture office. Though he wouldn’t return to Mexico for decades, the country undoubtedly left its mark on the young architect, both in his practice and his imagination (he even went on to publish Mexican Architecture: Domestic, Civil & Ecclesiastical in 1926).

Perhaps more than anything, however, the architect’s chief inspiration was San Antonio itself. His designs, especially the 200-plus homes he created in neighborhoods like Olmos Park, Monte Vista, Alamo Heights, and Laurel Heights, were adapted for life in Central South Texas.

More in San Antonio Real Estate

“He shaped his building with considerations of climate, site, the nature of materials, the requirements of sound construction, and influence of economics,” writes Coote in The Eclectic Odyssey. “His houses were very well planned for lifestyles he understood and shared.”

“He’s the truest to neoclassical in San Antonio,” Valentine adds. “And he set the standard with those big stately mansions.”

The 2-acre property was designed by Atlee Ayres, and is considered a crown jewel of San Antonio real estate.

Courtesy, Phyllis Browning CompanyFrom Monte Vista mansions to swanky skyscrapers

Among the characteristics of those “big stately mansions” were fluted columns, flat-roofed sleeping porches, and deep porte-cochères, all designed to maximize the breeze coming into the house. Even the angle of the home itself was selected to minimize the South Texas heat, such as the Thomas Hogg house, located one block west of Trinity University. Built in 1923 with an addition by Ayres’ and his son, Robert, in 1948, it’s considered “a key house in the history of domestic architecture in San Antonio,” notes the Society of Architectural Historians. Among its many influential details is the use of “dark red or mahogany floor tiles,” which Ayres was inspired to use after a trip to Los Angeles.

The late Marion Koogler McNay’s home remains a focal point for the grounds of the McNay Art Museum.

Kin Man Hui /Staff photographerThis attention to detail is also seen in the Atkinson-McNay house, arguably Ayres’ most famous residential work. Now home to the McNay Art Museum, the original building was “bent and angled in plan to expose the rooms to the prevailing Gulf breeze from the southeast,” writes Coote.

Ayres also designed the Atkinson-McNay house as a celebration of indoor-outdoor living. Along with the magnificent interior courtyard, Ayres had a “careful concern for comfort in semitropical San Antonio,” and designed the home to integrate the interior rooms with the gardens using doors, windows, loggias, and balconies.

“Look at the materials they use, and the way they have the circulating air, the climate of the city, it’s not just a style, it makes sense about how the building is organized in the interior,” says Valentine. “It has more to do with the basic architecture rather than copying the look.”

Along with a talent for architectural design, Ayres had two other things that were critical to his success: timing and connections. The turn of the century brought an influx of new, wealthy residents to San Antonio, many of whom eschewed the tony King William district for largely undeveloped “suburbs” like Olmos Park and Monte Vista. The introduction of these newcomers was coincidentally timed with the launch of Ayres’ architecture firm, which he founded in 1898.

Even his work on the Atkinson-McNay house came after Ayres heard a rumor that the wealthy oil heiress Marion Koogler McNay was relocating to San Antonio and so he proactively wrote her a letter. “If you would give us some idea of your requirements,” Ayres wrote to the heiress, “we would be glad to send you some sketches.”

“He obviously had very good contacts,” Valentine says.

An Alamo City legacy

His work extended beyond the residential streets of San Antonio, and beginning in the 1920s, Ayres began to take on more commercial projects, including the famed Smith-Young Building in 1926 and the aforementioned “Taj Mahal” in 1931. Contracts with the State of Texas took him outside the Alamo City limits, with projects across the state, including a remodel of the Texas State Capitol.

By his death in 1969, he had designed numerous Texas courthouses, helped pass legislation, authored books, and was still practicing at the age of 96 when he died.

What places Ayres among the architectural masters of his time was not his prolificness or proficiency, but his ability to find what was beautiful and adapt it. His designs, whether Craftsmen or English Tudor or Mediterranean, stayed true to their style but were designed for life in South Central Texas. By designing buildings for real life, he in effect helped shape San Antonio’s quintessential look.

“Look at the materials [the Ayres] use, and the way they have the circulating air, the climate of the city, it’s not just a style, it makes sense about how the building is organized in the interior. It has more to do with the basic architecture rather than copying the look,” Valentine explains.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Cootes, who writes, “Atlee had a special talent for understanding what those created the styles found beautiful.”

https://www.mysanantonio.com/real-estate/article/Atlee-Ayres-architect-San-Antonio-mcnay-freeman-16801054.php